In 2018, the Swiss Federal Government published the draft text of a Swiss-EU agreement intended to adapt the institutional rules of five existing EU Agreements. Since then, an internal Swiss debate has been going on relating to the draft text and possible avenues for the future. What options have been put on the table and where are the difficulties?

Author: Prof. Dr. Christa Tobler, LLM

Download blog as PDF

In search of its position

Following a consultation process relating to the draft Institutional Agreement as published in December 2018, the Federal Council (Federal Government of Switzerland) in June 2019 sent a letter to the president of the European Commission, stating, among other things:

«While the Federal Council confirms its intention to find solutions to the institutional questions with the EU and believes the outcome of the negotiations to be largely in Switzerland's interests, it will be necessary, in order to present the agreement to Parliament:

-to clarify that the provisions on state subsidies in the draft institutional agreement have no ‘horizontal effect’, in particular on the Free Trade Agreement of 1972 prior to its possible modernisation; this could be achieved, for example, by removing the last consideration from the draft decision of the FTA joint committee.

-to provide legal certainty for the current level of wage protection in Switzerland.

In addition, concerning the Citizens’ Rights Directive, Switzerland wishes to clarify that no provision of the institutional agreement shall be interpreted as an obligation for Switzerland to adopt the directive, or any related further developments, and that a possible adoption of the directive by Switzerland shall only be achieved by means of negotiations between the parties.

Based on these elements, the Federal Council is willing to engage in dialogue with the Commission over which you preside in order to reach a mutually satisfactory solution.»

Since then, no progress has been made between the negotiation parties, due to the fact that Switzerland is still trying to define its position on how to deal with the above-mentioned points. Different political parties and other stakeholders take exceedingly different views on the matter. This blog post first of all summarises the options as described more extensively in an article of the blog’s author, written in the German language and published in January 2020. It then adds some remarks on the complexity of the present situation.

Overview on the main options

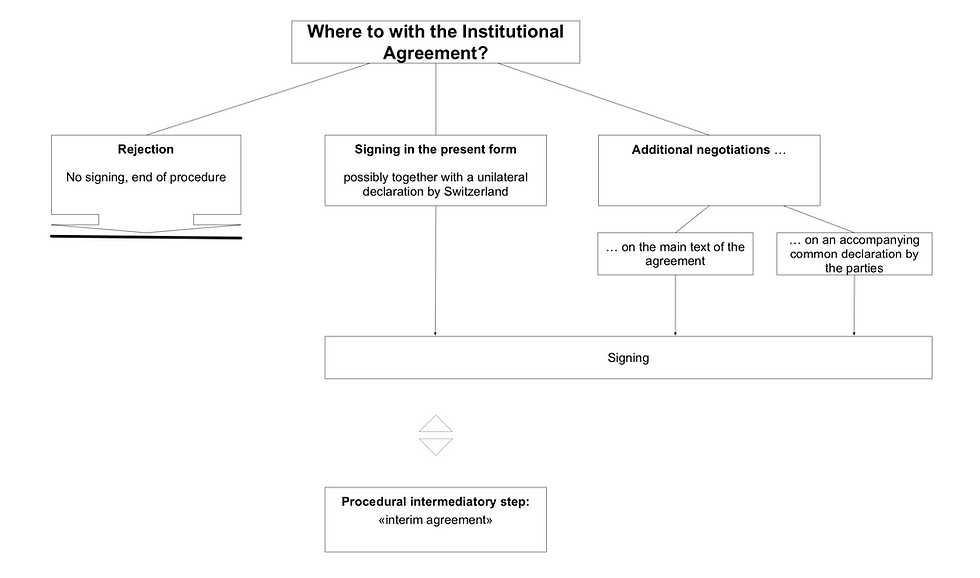

The main options discussed in Switzerland at present are the following:

Rejection of the agreement altogether is a hallmark of the Swiss People’s Party who considers it a colonial treaty that undermines direct democracy, disregards Swiss independence, neutrality and federalism and endangers Swiss welfare. In academia, the former president of the EFTA Court and retired law professor, Carl Baudenbacher, is the most prominent critic of the the draft Institutional Agreement. His criticism is levelled in particular at the dispute settlement mechanism provided for in the draft text, which is modelled on the EU-Ukraine Agreement and provides for an arbitration panel and an interpretative role of the Court of Justice of the European Union where the bilateral law at issue is derived from EU law in term of its substance.

Conversely, signing of the Institutional Agreement in its present draft form is advocated by the Green-liberal Party of Switzerland and in academia by the retired law professor, Thomas Cottier. The latter argues notably that the Institutional Agreement would not only be beneficial for Switzerland, but also is perfectly acceptable from the perspective of a modern understanding of sovereignty. According to Cottier, it might help if Switzerland were to add a unilateral declaration to the treaty text or to agree with the EU on a common declaration.

Others advocate additional negotiations with respect to the text of the draft Agreement. For example, in April 2019, the parliamentary Committees for Economic Affairs and Taxation of the Council of States and the National Council each decided to submit a motion with the aim of instructing the Federal Council to “conduct additional negotiations with the EU or take other appropriate measures to improve the institutional agreement with the EU”. A minority of the committees had opposed the motions, arguing that this would not strengthen the position of the Federal Council, but on the contrary would weaken it. Indeed, the Federal Council requested that the motions be rejected. Nevertheless, both have since carried.

In academia, I belong to those who advocate additional negotiations, but then not with respect to the main body of the draft text (which course of action the EU has repeatedly ruled out) but rather with a view to formulate common declarations regarding the three issues mentioned by the Federal Government as being in need of clarification. To recall, the three issues concern the Union Citizenship Directive, labour protection and state aid. The concerns of the Federal Government, as identified through process of consultations are the following:

Union Citizenship Directive: Almost ten years ago, the EU told Switzerland that the bilateral Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons (AFMP) should be updated in view of EU Directive 2004/38. However, the Swiss Federal Government refused, and the EU could not do much about it, given that the AFMP in its present form does not provide for a legal obligation to update its legal acquis in the light of more recent EU law. During the negotiations on an Institutional Agreement, the EU maintained that the Directive should be included among the legislation that would, in the future, fall under a system of dynamic updating similar to that under EEA law. Conversely, Switzerland argued that the Directive should not be covered by that system. The draft text of the Institutional Agreement does not explicitly mention the Directive, which means that it is, in principle, subject to the new system of dynamic updating. However, according to the AFMP, the part of this agreement to which the issues regulated by the Directive belongs (namely the main body and Annex I) cannot be updated through a simplified mechanism in the Joint Committee but needs to be addressed in a formal revision procedure. In the present writer’s opinion, this leaves room for negotiations on the question of how much of the Directive is indeed relevant from the perspective of the AFMP. After all, certain provisions of the Directive clearly embody CJEU case law based on the concept of Union citizenship, which as such is not part of the EU-Swiss bilateral law. This concerns most notably the equal treatment rule under Art. 24 of Directive 2004/38, as far as it extends to social assistance. In Switzerland, there are pronounced fears of extending equal treatment in this field beyond the scope of the present bilateral law. Against this background, my suggestion for a common declaration aims to secure negotiating space in the framework of the updating procedure. It is, quite simply: Union Citizenship directive: The parties note that an adaptation of the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons to the relevant provisions of Directive 2004/38 must be made in accordance with Art. 18 AFMP by way of a formal revision of the Agreement.

Labour protection: Here, the concerns relate to the protection of workers posted by EU employers in Switzerland in term of, among others, their salaries. Following the conclusion of the AFMP, Switzerland designed an elaborate system of measures intended to ensure that Swiss employment standards are complied with in the case of posting. The EU has long complained that some of these measures infringe the AFMP (meaning even before it is updated with new institutional rules). Among these measures is, notably, an obligation of most foreign employers to register activities planned in Switzerland eight days before the work begins. The idea behind this is to give the authorities time to organise controls. Under the current EU law on posting, notably Directive 2014/67, an obligation to register is acceptable but without a waiting period. However, neither the Directive just mentioned nor the more recent Directive 2018/957 that amends the EU law on posting are part of the legal acquis of the AFMP. Because Switzerland, being a high price and high salary country, had expressed particular concerns on this matter in the negotiations, the draft Institutional Agreement provides for certain special rules for Switzerland that will apply in the framework of updating the AFMP to the new EU law on posting. These include, for example, the right to maintain a waiting period in the context of registration, though in a more limited fashion. Even so, the Swiss labour unions are firmly opposed to such rules, fearing in particular the influence of the CJEU in the framework of the dispute settlement mechanism. They therefore insist that the issue of labour protection should remain outside the Institutional Agreement. In my opinion, given that the issue is covered by the AFMP in its present form, it is illusionary to want to keep it out of the Institutional Agreement entirely. Instead, the present writer’s suggestion is a common declaration emphasizing, among others, the room for action that remains for Switzerland even under the new rules: Labour protection in the case of posting: The Parties recognise that Switzerland, due to its high level of wages, is in a special situation with regard to the posting of workers, in which the principle of ‘equal pay for equal work’ is of particular importance and must apply permanently. The parties emphasize that the provisions on occupational health and safety measures included in the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons offer room for legislative action for effective protective measures over and above the special regulations permanently granted to Switzerland in the Institutional Agreement. Switzerland may continue to entrust checks on compliance with labour regulations to the social partners.

State aid: Under the present bilateral law, there are only few and little developed competition rules. In the course of the negotiations about the Institutional Agreement, the EU raised the issue of the regulation of state aid. Whilst the Agreement on Air Transport contains state aid rules, these are not at the level of modern EU law in this field. Accordingly, the draft Institutional Agreement provides for their adaptation. This is not considered a problem in Switzerland. Conversely, the Swiss Cantons are afraid of losing valuable competences in view in particular of a draft Joint Committee decision attached to the Institutional Agreement. On a more general level, the draft decision notes that, among others, the Free Trade Agreement, concluded in 1972, should be modernized. As a first step in this direction, a draft decision of the Joint Committee in charge of that agreement provides for first steps in this direction as far as state aid is concerned. The Swiss Federal Administration is of the opinion that one passage in the preamble to thedraft decision in particular might have immediate effects, possibly even outside the Free Trade Agreement. This passage reads (my translation): “Considering that Switzerland and the European Union have agreed that, within the meaning of Article 31 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, the provisions of Part II of the Institutional Framework Agreement constitute a subsequent agreement between the Parties which is relevant for the interpretation of Article 23(1)(iii) of the Agreement and that this interpretation now guides its application […].” Against this background, my suggestion for a common declaration tries to limit the effect notably of the draft decision: State aid: The Parties note that, at the time of signature of this Agreement, the provisions of Part II, Chapter 2 of the Institutional Agreement apply exclusively to the Agreement on Air Transport concluded between the Parties on 21 June 1999. The Parties further confirm that the decision of the Joint Committee under Article 29 of the Agreement between the Swiss Confederation and the European Economic Community concluded in Brussels on 22 July 1972, which is currently in draft form, shall be taken up by the Joint Committee as soon as possible after the conclusion of the Institutional Agreement with a view to its formal adoption. Once it enters into force, it will have legal effects only for the Free Trade Agreement.

Finally, it has been suggested that, should it prove politically impossible to come to a timely agreement with the EU, the Swiss Government should strive for an interim agreement before actual failure occurs through rejection by the Federal Council, parliament or the people in a referendum. This suggestion has been made by Michael Ambühl, professor of negotiation and conflict management at the Technical University in Zurich and his assistant, Daniela Scherer. The aim would be to find a way out in the form of an interim solution in order to maintain the good bilateral relations and to cushion the negative consequences of the (provisional) non-signature of the Institutional Agreement, by means of an interim agreement, e.g. in the form of a low-threshold Memorandum of Understanding. According to Ambühl and Scherer, the partners could agree that, on the one hand, the updating of existing agreements will continue in the usual framework and, on the other hand, that Switzerland will refrain from demanding new market access agreements for the time being. As a sign of good will and in order to decouple political conditionalities, Switzerland could be significantly more generous in its cohesion contributions. Furthermore, the intention to continue the negotiations as soon as the time is ripe could also be stated. Following Ambühl and Scherer, such a course of action would help prevent pinpricks from the EU, such as those discussed in the next section of the present blog.

A complex situation …

It is unclear at this point in time which way the Swiss Government will move. Matters are complicated by the fact that, on a political level, the issue of the Institutional Agreement is linked to a number of other issues which shall be touched upon briefly at the end of this blog.

First, the issue of the stock exchange equivalence: though in terms of subject matter not linked in any way to the Institutional Agreement, the EU Commission in 2017 began to make a political link, announcing that it would renew its equivalence decision regarding the Swiss stock exchange regulations only if Switzerland would take positive steps towards the Institutional Agreement. Having decided in favour of equivalence on a temporary basis on two occasions, the EU Commission in summer 2019 did not renew its decision. According to the Swiss Federal Government, this breaches WTO law (namely the GATS). As a reaction, the Government barred Swiss shares from being dealt in EU stock exchanges. Further, the Swiss Federal Parliament, in retaliation, has decided that the next tranche of cohesion payments made by Switzerland in favour of projects in financially weaker EU Member States will not be paid “if and as long as the EU adopts discriminatory measures against Switzerland” (my translation into English).

More recently, the EU Commission announced that without the Institutional Agreement, it will no longer be prepared to update agreements following the practice of the parties in the past years. Among others, the Agreement on the Mutual Recognition of Conformity Assessments (MRA) has been updated very regularly to include new technical EU rules, even though there is no legal obligation to do so under the present system. The next update concerns medical devices. Whilst part of the new EU-Regulation 2017/745 has already been incorporated into the MRA, a large part is still missing. In the EU, this part will apply as of 26 May 2020. The EU has stated that is not willing to agree to an updating decision in the Joint Committee. At the same time, it argues that, absent this update, the entire chapter on the mutual recognition of conformity assessments can no longer be applied. In the present writer’s opinion, this is a flagrant breach of Art. 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, according to which a party may not invoke the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty.

The month of May 2020 is also important with respect to another issue that is crucial for Switzerland: At present, Switzerland is revising its data protection law in order to bring it in line with the renewed Data Protection Convention of the Council of Europe and with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 (GDPR). Under this Regulation, the EU Commission has to report until 25 May 2020 about, among others, adequacy decisions with respect to third countries. Switzerland at present benefits of a decision that was issued under the previous law and that needs to be renewed. There is no legal link with the Institutional Agreement but a positive development in that latter context is most likely to help.

Finally, neither is there a legal link with Brexit, but there are parallels as the Withdrawal Agreement also contains institutional rules. For example, the model for the settlement of disputes is largely similar to that under the draft Swiss-EU Institutional Agreement. Further, the EU will soon have to engage in negotiations about the legal relationship with the UK after the transitional period under the Withdrawal Agreement. From its point of view, it would be good to have the EU-Swiss Institutional Agreement out of the way by that time. However, whether that will be possible depends largely on the steps that the Swiss Federal Government will take in the present complex situation in which very different issues have proven to be connected.

At this point in time, only one thing seems clear: right now, the Federal Government will not take any further steps vis-à-vis the EU due to yet another fateful date in the month of May 2020: on 17 May, a vote will be held in Switzerland on a popular initiative aimed at abolishing the free movement of persons. If won, it would most likely mean that the Government would have to terminate the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons, which in turn would mean that a number of other agreements would also cease to exist because they are linked to each other. In fact, the five agreements to which the Institutional Agreement is meant to apply, would all be gone, thereby in effect obviating the need for the latter agreement. From the Swiss Federal Government’s point of view, it is necessary to have that threat out of the way before moving on. It remains to be seen what the direction of that movement will be and whether it will reflect a clear vision for Switzerland’s relationship with the EU – a vision that, according to Jenni, appears to be missing at present.

Author

Prof. Dr. Christa Tobler, LLM, Professor of European Union law at the Europa Institutes of the Universities of Basel (Switzerland) and Leiden (the Netherlands)

How to cite

Tobler, Christa (2020): Switzerland-EU: Whereto with the draft institutional agreement? Blog. Efta-Studies.org.

Comments